Cybercrime

,

Cybercrime as-a-service

,

Fraud Management & Cybercrime

Numerous Impediments Remain If Administrators Attempt to Reboot the Operation

The notorious ransomware-as-a-service group LockBit, disrupted by law enforcement this week, had been developing a new version of its crypto-locking malware.

See Also: OnDemand | Understanding Human Behavior: Tackling Retail’s ATO & Fraud Prevention Challenge

So said Tokyo-based cybersecurity firm Trend Micro, which contributed to the international LockBit investigation and takedown spearheaded by Britain’s National Crime Agency.

The ransomware operation was working on the “next-generation” crypto-locking malware, dubbed LockBit-NG-Dev, “which could be an upcoming version the group might consider as a true 4.0 version once complete,” Trend Micro said.

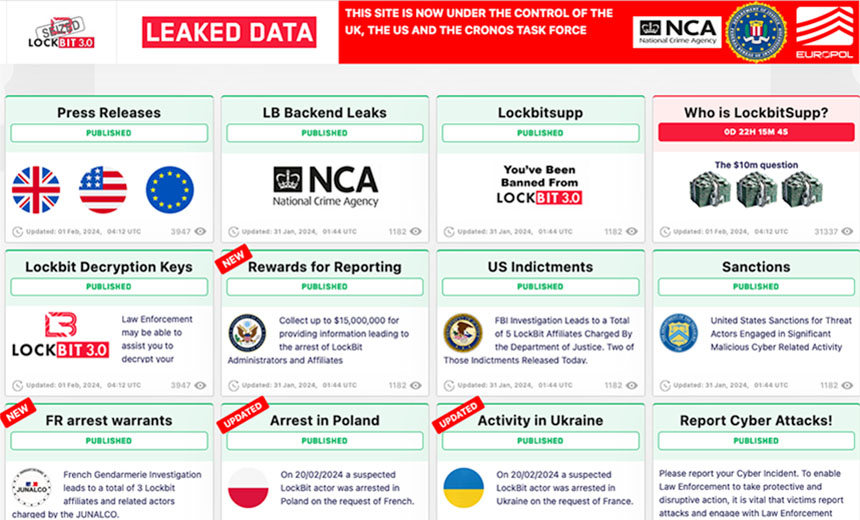

The status of those efforts remains unclear since the NCA and FBI announced Tuesday that via “Operation Cronos,” 10 countries had worked jointly to infiltrate and on Monday shut down the infrastructure used by “the world’s most harmful cybercrime group,” backed by arrests and indictments of alleged affiliates and money launderers.

Whether LockBit attempts to reboot or if its brand might be permanently burned remains an open question. Regardless, numerous security experts have lauded the disruption, saying it will cause major and likely terminal operational headaches for LockBit’s administrators, contractors and affiliates.

Until the takedown, LockBit remained a major player. In 2023 and so far this year, LockBit received the second-highest amount of traceable ransom payments of any ransomware group, said blockchain analytics firm Chainalysis.

Last year, LockBit listed 928 organizations on its data leak site, accounting for 23% of the 3,998 victims listed across all such leak sites, said Palo Alto Networks’ Unit 42. How many more victims the group didn’t list, in part because they paid it a ransom, isn’t clear.

Mounting Problems

Despite the group’s illicit profit-making prowess, one major impediment was that due to “a number of logistical, technical and reputational problems,” it hadn’t produced a major new version of its crypto-locking malware for affiliates in two years, Trend Micro said.

“With the seeming delay in the ability to get a robust version of LockBit to the market, compounded with continued technical issues, it remains to be seen how long this group will retain their ability to attract top affiliates and hold its position,” Trend Micro said. “In the meantime, it is our hope that LockBit is the next major group to disprove the notion of an organization being too big to fail.”

LockBit once stood apart from other ransomware groups in part due to the speed and sophistication of its crypto-locking malware, which offered “a simplified, point-and-click interface for its ransomware, making it accessible to those with a lower degree of technical skill,” the U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency reported last year.

“From a purely technical side, what made LockBit special compared to other competing ransomware packages was that it used to have self-spreading capabilities,” Trend Micro said. “Once a host in the network becomes infected, LockBit is able to search for other nearby targets and to try and infect them as well, a technique that was not common in this kind of malware.”

On the PR front, the group’s public-facing persona, LockBitSupp – short for “LockBit Support” and reportedly run at least in part by the group’s actual leader – regularly boasted of his outfit’s prowess at the expense of rivals, seeking to burnish the brand and attract fresh affiliates. He promised affiliates would get paid before the core operators and receive 80% of every ransom their victim paid, or 50% to 70% if LockBit handled the negotiations, Trend Micro reported.

LockBitSupp also backed stunts, such as promising to pay $1,000 to anyone who got tattooed with the group’s logo, and offering a $1 million bounty to anyone able to reveal his true identity.

Security experts said the crypto-locking malware attracted all manner of affiliates and sported close ties to other Russian crime syndicates. Research released by Mandiant in 2022 suggested Russia’s notorious Evil Corp had used LockBit to evade U.S. sanctions. Chainalysis tracked cryptocurrency donations made by one of LockBit’s administrators “to a pro-Russia self-proclaimed military journalist based in Sevastopol known as Colonel Cassad.”

Multiple Versions

Security experts said LockBit previously released multiple versions of its ransomware:

- LockBit version 1.0 was released in January 2020 and originally known as “ABCD” ransomware.

- LockBit version 2.0, aka “Red,” was released in June 2021 together with StealBit, the group’s primary data exfiltration tool.

- LockBit Linux was released in October 2021 to infect Linux and VMWare ESXi systems.

- LockBit version 3.0, aka “Black,” was released in March 2022 and leaked six months later by the group’s disgruntled developer, leading to multiple knockoffs.

- LockBit Green was released in January 2023 and heralded as being a major new version, which security experts quickly dispelled, finding it to be a rebranded version of a Conti encryptor.

Trend Micro said its teardown of the as-yet-unreleased LockBit-NG-Dev revealed that while it has similarities with the previous lockers, “this new version seems to have been written in .NET and possibly compiled using CoreRT, which is different from the usual C/C++ language used for past versions.”

The security firm said the malware offers fast, intermittent and full encryption modes. “Files are usually encrypted under fast mode to speed up encryption – an option commonly favored by affiliates – but it can be configured to perform different modes based on file extensions,” the firm said. LockBit first added an intermittent encryption option in version 2.0 of its crypto-locker.

Lagging Updates

LockBit last released a major new version of its ransomware crypto-locker two years ago.

The release of LockBit Green in January 2023 appeared to be a hedge by the group, which had been known for releasing a major new version each year, said ransomware researcher Jon DiMaggio, chief security strategist at threat intelligence firm Analyst1. The group’s problems were mounting in part because as LockBit’s popularity exploded and it attracted numerous affiliates, the organization – “run by an ego-driven CEO that has massive insecurities” – failed to retain technical talent or successfully scale its infrastructure, DiMaggio told Information Security Media Group last year. As a result, services that affiliates expected, such as new versions of the malware or the reliable, automatic leaking of stolen data after a victim refused to pay, didn’t happen.

Further poor management choices by the group’s leadership triggered a falling out with a key developer, who then exited over nonpayment for work provided, leaked source code and publicly denigrated the group, DiMaggio said. The loss of that developer appeared to leave the group without any ability to rapidly develop a major new version of its malware.

Subsequently, LockBit appears to have engaged in a smokescreen. Researchers Yelisey Bohuslavskiy and Marley Smith of threat intelligence firm RedSense told ISMG the group’s LockBitSupp persona had conducted interviews with journalists and issued provocative statements, especially via Twitter, designed to keep the group in the public eye. At the same time, the ransomware group had signed up numerous low-level affiliates, which the researchers reported had been largely ineffective at amassing ransom-paying victims but still publicly connected the group to active attacks. That was the smokescreen.

Behind the scenes, Smith said, LockBit was working with “ghost groups” – contracting with highly skilled hackers, aka pen testers, who worked either independently or with other ransomware groups such as Zeon. Smith said many of these highly skilled pen testers had previously worked for the notorious Russian-speaking Conti ransomware group that folded after it publicly backed President Vladimir Putin’s war of conquest against Ukraine, which led many Conti victims to refuse to pay it a ransom.

Conti Talent Bolstered LockBit

Using ghost groups enabled LockBit to compensate for its own lack of technical talent or skilled affiliates and “to maintain a certain level of mystique and power” needed to bolster the brand and to continue scaring victims into paying, Smith said.

“While low-tier affiliates were posting on Twitter, the real professionals from Conti were attacking high-profile targets all over the world,” resulting in numerous victims quickly paying up and never getting listed on LockBit’s data leak site, the RedSense researchers said in a new report.

This week’s law enforcement takedown disrupted that state of affairs. Experts said a LockBit reboot remains an unlikely possibility owing to the resulting loss of face and the group no longer having the in-house technical talent it would need to rebuild its infrastructure. “Most likely, LockBit will try to dump old data – the tactic that is used by every group after a takedown, but this won’t bring any results except for media speculation,” the RedSense researchers said.