Finance & Banking

,

Fraud Management & Cybercrime

,

Fraud Risk Management

It’s Time for Big Tech to Be Held Accountable for Rampant Online Fraud

From account takeover threats to fake investment schemes, you don’t have to spend much time on social media before you stumble across a scam. But if you try to report these bad actors to social platforms such as Facebook, you may have a hard time getting through.

See Also: The External Attack Surface Is Growing and Represents a Consistent Vulnerability

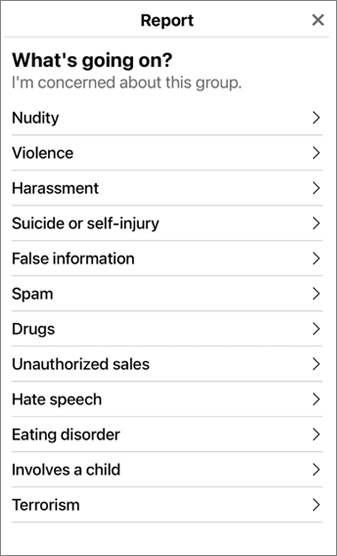

In fact, if you try to report scam content to Facebook parent company Meta, you won’t find “scam” or “fraud” as a reporting option.

Troy Huth, director of Auriemma Roundtables in San Antonio, Texas, recently recounted how he tried to report a scammer to Meta: “I’ve picked what I thought was the closest thing and had them respond back that they didn’t see this behavior occurring and left the profile active.” Even worse, after he outed the scammers on Facebook, they banded together to report him for “harassment,” and Meta subsequently took down his profile, he said.

Experts say that a large percentage of scams originate on social media. A report by the Federal Trade Commission says that 1 in 4 people who have reported losing money to fraud since 2021 said the scam started on social media. A UK Finance analysis of nearly 7,000 authorized push payment fraud cases finds that 70% of scams originated on an online platform.

Despite these threats to users, Huth said it doesn’t appear that Meta cares that its “platform is blatantly used to promote scams and financial crime.” Ken Palla, fraud expert and former director of MUFG Bank, said that despite initials talks and steps, social media companies have yet to take concrete actions against scammers.

“Every day I am reading about different initiatives to help stop scams,” he said. “I see today Meta and some other internet platforms are talking about ‘will work to find ways to fight back against the tools used by scammers,’ but most of us have the most difficult time getting internet platforms to actually take down scam sites.”

Fraud expert Frank McKenna at Point Predictive recently filed several reports about Yahoo Boys groups on Facebook that were recruiting new members, selling methods to scam people and providing instructions on how to extort victims, including providing face-swapping software to deepfake victims in video calls. McKenna said he chose Meta’s “unauthorized sales” complaint form, but Meta “declined to remove every single one of them, saying it doesn’t go against Facebook’s guidelines. I guess recruiting people into criminal organizations, selling fraud services and doing things like committing extortion against juveniles is not against Facebook’s guidelines.”

But within a week, Meta took action. “I am happy to report that Facebook finally removed Bombin and Billin – one of the largest Yahoo Boys fraud groups on Facebook with over 194,000 members!” McKenna posted on LinkedIn on Wednesday.

The Time for Accountability Is Now

While the system works sometimes, the overarching problem is that Meta and other social platforms have little to no accountability – or regulatory oversight. Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, which dates back to the internet’s infancy in 1996, says that Congress explicitly protects social media platforms from liability for the content that users post on their sites.

Unfortunately, social media has become a much darker place over the past two decades with the rise of pig butchering, money muling, crypto scams, disinformation and hate speech – just to name a few. Last month, in a bipartisan effort, two House representatives introduced a bill to kill Section 230, in an effort to force Congress to reform the law.

Not surprisingly, social media companies would prefer to keep things as they are.

Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers, R-Wash., said that Congress has introduced nearly 25 bills to change the law over the past four years. “Many of these were good faith attempts to reform the law, and Big Tech lobbied to kill them every time,” she said. “These companies left us with no other option.”

Efforts by other countries to regulate scams on social media haven’t been much more successful. In November 2023, internet platforms in the United Kingdom signed the Online Fraud Charter. Since then, there has been little action on this front, and no concrete steps have been taken to protect users from scammers.

Australia is trying to get banks, telecoms and internet platforms to work together to stop scams. This week, Australia announced the “intel loop,” which will share scam information between these entities and the government.

Why isn’t more being done? Let’s be honest: Scams and money muling aren’t top priorities. While everyone agrees these activities are undesirable, the financial impact isn’t significant enough to drive coordinated regulation and remediation.

Tech companies still lack proper reporting mechanisms for scams, making voluntary action unlikely. Monetary penalties are the only effective incentive.

The banking and financial services industry continues to tackle fraud on all fronts, but its efforts alone will not solve the problem. Tech companies must have skin in the game, and that starts with facing the same liabilities as banks and investment companies. Without their involvement, the public remains at high risk of online scams. Each consumer loss may be comparatively small, but the financial and emotional impact of falling for a scam can be many times greater. Consumers the ones who need more protection – not Big Tech.