Agentic AI

,

Artificial Intelligence & Machine Learning

,

Endpoint Security

Closed AI Loops Are Concentrating Power – and Creating Room for Startups

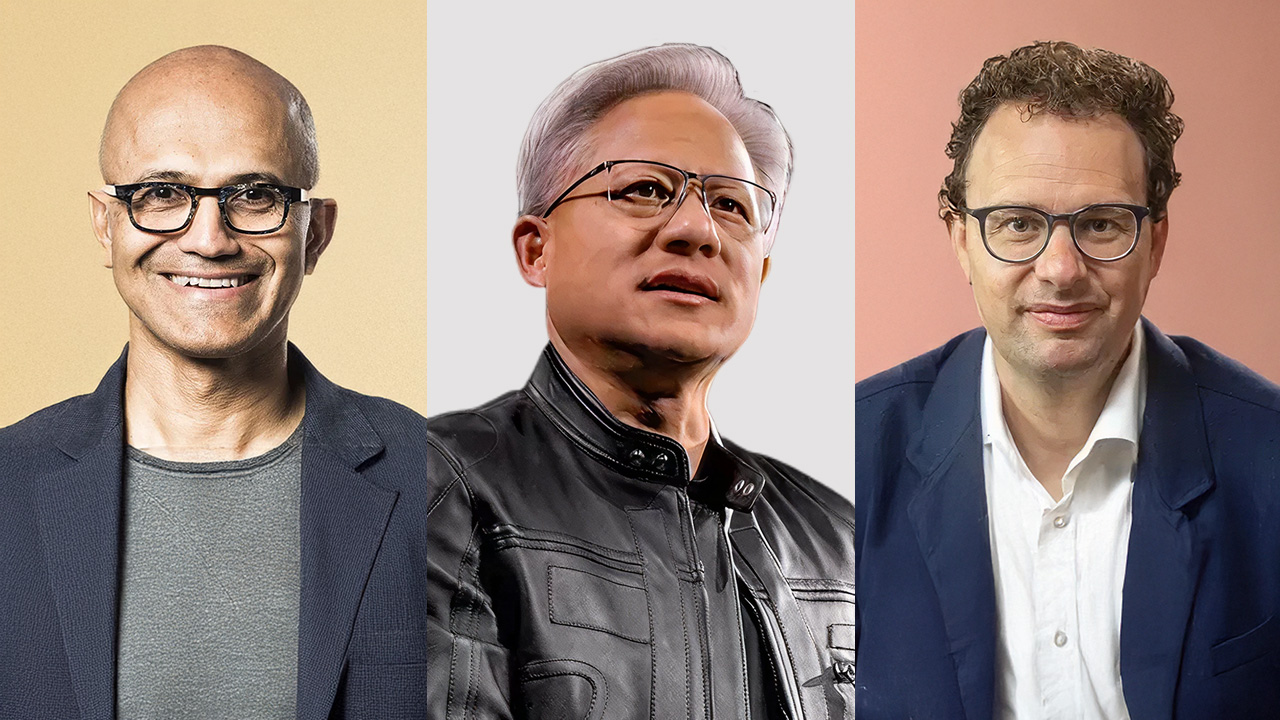

When Microsoft, Nvidia and Anthropic formalized their latest partnership last month, Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella distilled the logic behind it into a single line: “We are increasingly going to be customers of each other.”

See Also: A CISO’s Perspective on Scaling GenAI Securely

It’s arguably the best way to describe the latest tie-up in the artificial intelligence world. Anthropic would commit tens of billions of dollars to Microsoft’s cloud. Microsoft and Nvidia plan to invest billions back into Anthropic. Nvidia will co-design hardware optimized for Anthropic’s next generation of AI models, and Microsoft will distribute those models across Azure and its enterprise products.

The companies are, quite literally, buying from and reinforcing each other. And that closed circuit partnership sends a clear signal that the power behind AI is consolidating.

“This deal is part of a broader move toward tightly coupled, capital-intensive AI ‘partnerships’ where models, cloud and chips are bound together via massive, multi-year commitments,” said Arun Chandrasekaran, distinguished vice president analyst at Gartner.

This structure accelerates frontier innovation, Chandrasekaran warned, but it “creates confusing incentives, inflating valuations and makes it hard to discern real market demand.” One of the big questions for the tech industry and regulators is: What does this Big Tech deal mean for AI startups?

The Anatomy of the Deal

At its core, the deal is both financial and infrastructural and, perhaps more consequentially, architectural. It binds together three of the most influential players in the AI stack: a model lab – Anthropic; a cloud-service provider – Microsoft; and a hardware supplier – Nvidia.

Anthropic, the startup behind the Claude family of large language models, has committed $30 billion to purchase Azure compute over multiple years, including the option to scale to one gigawatt of Nvidia-powered data-center infrastructure. Microsoft, in turn, is investing $5 billion in Anthropic, while Nvidia is putting in $10 billion, as confirmed by Microsoft’s announcement.

In return, Anthropic’s frontier models, including Claude Sonnet 4.5, Claude Opus 4.1 and Claude Haiku 4.5, will become the “only frontier model available on all three of the world’s most prominent cloud services” across Microsoft’s enterprise distribution channels: Azure via Foundry and Microsoft’s Copilot suite – GitHub Copilot, Microsoft 365 Copilot and Copilot Studio.

From Anthropic’s side, committing $30 billion in cloud spend is a bet that large-scale, long-term compute capacity will remain necessary – and advantageous – to develop increasingly capable models.

From Microsoft’s and Nvidia’s side, the deal is both defensive and expansive. Microsoft, after reconfiguring its earlier partnership with OpenAI, appears to be hedging its AI bets by anchoring with multiple model providers rather than depending on a single company. This reduces technology-supply concentration risk for Microsoft while strengthening its control over the enterprise AI stack through Azure and Copilot integrations.

For Nvidia, the deal serves as a demand anchor for its next-generation AI hardware. By co-engineering hardware and software with Anthropic – optimizing models for Grace Blackwell and Vera Rubin systems – Nvidia ensures its chips remain central to frontier-model training and inference workloads.

That arrangement is not a one-off anomaly. Over the past two years, the AI industry has begun to assemble similar loops at its highest tiers.

Microsoft’s longstanding partnership with OpenAI operates on a similar axis: OpenAI depends on Azure for training and inference at scale, while Microsoft integrates OpenAI’s models into its products and underwrites the associated compute expansion.

Amazon structured its own version with Anthropic earlier, committing up to $4 billion to the model developer and securing Anthropic’s use of AWS Trainium and Inferentia chips.

Google had already invested $2 billion in Anthropic before that, alongside deep integration of Claude models with Vertex AI and Google Cloud infrastructure.

The logic behind these deals is straightforward. Frontier model developers need compute at a scale only cloud hyperscalers can provide. Cloud providers need differentiated models to stay competitive. Chipmakers need guaranteed demand for their most expensive silicon. Tie all three together, and the partnership becomes self-sustaining.

Chandrasekaran notes that these multi-billion-dollar alliances “haven’t yet attracted a lot of regulatory attention,” but that’s unlikely to last. Scrutiny will emerge, he says, when these arrangements begin to foreclose rival cloud providers or model developers, undermine local data-control regimes, or create cross-border dependencies that governments cannot ignore.

Are Startups Worried?

Vinay Goel, CEO and co-founder of Wald.ai, argues that these mega-alliances are “defensive moves, not kingmaking moves.” “When the large players form closed loops, it’s usually a sign they’re hedging against the next breakout technology … and strangely, that creates more oxygen for startups,” he said.

One of the loudest worries in the AI world is GPU scarcity. Surely, when companies tie up huge quantities of compute in long-term contracts, it would affect compute access or pricing for startups?

“Absolutely, and in a good way,” Goel said. “When big players hoard supply, they also industrialize the pricing. GPUs and frontier models have become commodities and startups love commodities.”

A Palo-Alto-based context intelligence company, Wald.ai processes millions of inferences across providers. Goel said they “never had cheaper access to world-class models, and we don’t carry the burden of spending hundreds of millions to train them.”

Sameer Agarwal, co-founder and CTO of Deductive AI, is cautiously optimistic. He agrees that startups now have the leverage to build on top of increasingly capable base models without the prohibitive cost of training them, but the pressure comes from strategic dependencies. “If access to cutting edge models is gated behind cloud commitments or specialized licensing, then smaller companies must be disciplined in choosing when to rely on closed models and when to build their own capabilities,” Agarwal said.

Startups, however, still have an edge – as long as they know what to innovate.

Enterprise buyers talk about wanting a single integrated stack, but “what they actually buy is best-in-class pieces that solve real pain,” Goel said.

Governance, observability, compliance, model auditing – these are not areas where enterprises are eager to trust a monolithic provider. Agarwal agrees. “The opportunity is still huge for companies solving real operational problems that require deep domain reasoning, not just raw model capacity.”

This gap between what enterprises say they want and what they actually buy is precisely where specialized startups can thrive. “This is the best time in history to build an AI startup as long as you’re not trying to out-train the giants. Out-innovate them in specific domains instead,” Goel said.