Between crossovers – Do threat actors play dirty or desperate?

In our dataset of over 11,000 victim organizations that have experienced a Cyber Extortion / Ransomware attack, we noticed that some victims re-occur. Consequently, the question arises why we observe a re-victimization and whether or not this is an actual second attack, an affiliate crossover (meaning an affiliate has gone to another Cyber Extortion operation with the same victim) or stolen data that has been travelling and re-(mis-)used. Either way, for the victims neither is good news.

But first thing’s first, let’s explore the current threat landscape, dive into one of our most recent research focuses on the dynamics of this ecosystem; and then explore our dataset on Law Enforcement activities in this space. Might the re-occurrence that we observe be foul play by threat actors and thus show how desperately they are trying to regain the trust of their co-offenders after disruption efforts by Law Enforcement? Or are they just playing dirty after receiving no payments from the victim?

What we are observing in the Cy-X threat landscape

Cyber Extortion (Cy-X) or Ransomware, as it’s more commonly known, is a topic that has garnered lots of attention over the past three to four years. Orange Cyberdefense has covered this threat extensively since 2020.

In the latest annual security report, the Security Navigator 2024 (SN24), research showed an increase of 46% between 2022 and 2023 (period of Q4 2022 to Q3 2023). Updating our dataset, we find that the actual increase is even higher with just under 51% increase. The updated number is due to the dynamic nature of the dataset; the ecosystem continuously changes and so we only became aware of certain leak sites and their victims once the research period had concluded.

Sadly, this just further compounds the reality. Predicting whether this level of increase will be maintained is difficult. Cy-X may have reached a saturation point, where we might see the Cy-X threat continuing at the 2023 levels. On the other hand, if we do follow the victim count patterns of the last years (lower numbers in the beginning of the year, increasing throughout the year), which would have the opposite effect, providing us with an ever-growing victim count once more. However, we believe that the Cy-X victim count levels will remain steady for now, and if we are fortunate, it could possibility point to a decrease in extortion victims. Nevertheless, we are a long way off from claiming victory.

Six months have passed since the end of the SN24 Cy-X dataset was discussed in the report, and a lot has happened during that time. The total number of victims for Q4 2023 and Q1 2024 tallies to 2,141 – nearly all the victims recorded for the whole of 2022, which was 2,220 victims. The volume of this victim count is remarkable given that two of the most active Cy-X groups were (attempted) to be disrupted during this time. Law Enforcement (LE) aimed to disrupt ALPHV in December 2023, where they showed resistance by “unseizing” themselves just days after. LE then took down LockBit’s infrastructure in February 2024, however, this only meant a few days’ downtime for LockBit since they also managed to get back online a few days after the initial takedown. Even though the two Cy-X operations seemed very resistant at the time, ALPHV (BlackCat) went offline at the start of March 2024, “exiting” the game with most likely a so-called exit scam.

Efforts to disrupt this volatile ecosystem – challenges due to short lifespans of Cy-X brands

No matter its effect, previous LE activities render important insights into Cy-X operations. One example is the dark number of the Cy-X crime, which is the number of victims we don’t know about because they aren’t exposed on the leak sites that we monitor. Knowing the dark number would help us complete the picture of the current Cy-X threat. Thus, the whole picture would include the actual number of victims that include our partial view of the victims that were exposed on the leak sites (our data) and the victim organizations we will never know about (the dark number). The takedown of Hive in 2023 revealed a higher number of victims than what we had recorded from their data leak site, where the actual number was 5 to 6 times higher. If we use the multiplier of six with the recorded victim count – 11,244 – from the start of January 2020 to end of March 2024, then the real victim count could be as high as 67,000 victims across all Cy-X groups.

Cl0p, who is the most persistent threat actor in our dataset, was very busy during 2023 and was responsible for 11% of all victims. However, for the last six months since that analysis only 7 victims were observed on the Cy-X group’s data leak site. Cl0p has flickered up in the past, mass exploiting vulnerabilities, only to pull back into the shadows, hence this might just be Cl0p’s modus operandi.

Security Navigator 2024 is Here – Download Now

The newly released Security Navigator 2024 offers critical insights into current digital threats, documenting 129,395 incidents and 25,076 confirmed breaches. More than just a report, it serves as a guide to navigating a safer digital landscape.

What’s Inside?#

- 📈 In-Depth Analysis: Explore trends, attack patterns, and predictions. Learn from case studies in CyberSOC and Pentesting.

- 🔮 Future-Ready: Equip yourself with our security predictions and research summary.

- 👁️ Real-Time Data: From Dark Net surveillance to industry-specific statistics.

Stay one step ahead in cybersecurity. Your essential guide awaits!

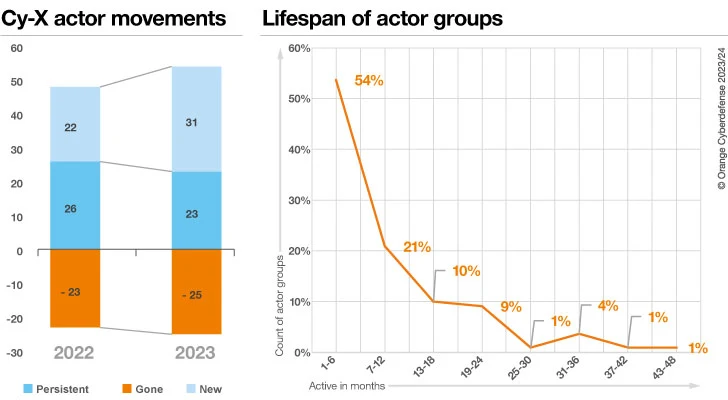

The total number of active Cy-X groups fluctuates over time, and certain groups persist longer than others. The Security Navigator 2024 report addressed this question by examining the year-on-year changes. Overall, 2023 did see a net increase in the number of active Cy-X groups compared with 2022. Generally, it’s a very volatile ecosystem with a lot of movement in it. Our research found that 54% of Cy-X ‘brands’ disappear after 1 to 6 months of operation. There were fewer Cy-X groups carried over to 2023, but the increase in the number of new Cy-X groups resulted in a net gain in activity. Further confirmation of the ephemeral nature of these groups. Ironically, LockBit3 and ALPHV were listed under the grouping of “Persistent” for 2023.

This research was performed as part of the examination of the effectiveness in defending against Cy-X. LE and government agencies from across the globe are working hard at eliminating Cyber Extortion as it is truly a global problem. In the last two and a half years we have seen a steady increase in LE activity, recording 169 actions combating cybercrime.

Of all documented LE activities, we saw Cyber Extortion addressed the most. 14% of all actions were attributed to be related to the crime of Cyber Extortion, followed by Hacking and Fraud with 11% each respectively. Crypto-related crimes claimed a share of 9%. Almost half of LE activities involved arrests and the sentencing of individuals or groups.

In our latest Security Navigator report, we wrote that “in 2023, we specifically noted increased efforts to take down or disrupt the infrastructure and hosting services threat actors (mis-)used.” With our updated dataset from the last 6 months, we do see an even higher proportion of the category “Law Enforcement disrupts”. Here, we collected actions such as announcements on kicking off international taskforces to combat Ransomware, LE tricking threat actors in providing them decryption keys, seizing infrastructure, infiltrating cybercrime markets, etc. While we have previously argued whether the actions that we do see executed most frequently, e.g. arrest and seizures might not be as effective, the two latest LE actions have been very interesting to follow.

In ALPHV’s case, who in first response seemed very resilient against the LE’s efforts to disrupt it, has fled the scene and (most likely) conducted an exit scam. This can greatly undermine “the trust” within the Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) ecosystem, there could be a short-term decrease in the number of victims as affiliates and other actors assess their risks. At the same time, there is a void to fill, and historically it does not take long for a new (re-)brand to fill this gap.

Similar to ALPHV, LockBit has claimed to have survived the initial takedown, but in the world of Cyber Extortion, reputation is everything. Would affiliates continue to do business with the “revived” LockBit not wonder if that may be a LE honeypot?

Re-victimization of Cy-X victims in form of desperation or affiliate crossovers

We know by now that the cybercrime ecosystem is a complex one, including many different type of actors, roles and actions. This is very true for the type of cybercrime we are monitoring – Cyber Extortion. Over the past decade, the ecosystem of Cybercrime-as-a-Service (CaaS) has really evolved and added several challenges to monitor this crime. One such challenge is that not one single threat actor executes one attack from beginning to end (the full attack chain).

As we see in the graph above, many different roles play a part in a Cy-X ecosystem, most notably the affiliates aka ‘Affiliate Ransomware Operator’. Affiliates are a critical part of the Cyber Extortion ecosystem as they enable the scale and reach of these cyber-attacks. This structure also adds a layer of separation between the Ransomware creators (Malware Author) and the attackers (Affiliate), which can provide a degree of legal and operational manoeuvrability for the developers. The affiliate model has contributed to the proliferation of Ransomware, making it a significant cybersecurity threat today. The nature of these associations does not lend itself to the assurance of exclusivity. In some cases, it seems that victim data propagates through the cybercrime ecosystem in ways that are not always clear.

When examining the victim listings on Cy-X data leak sites, we observe the re-appearance of victims. This is nothing new, we have been observing this phenomenon since 2020. But we finally have a big enough dataset to make an analysis on the sightings of re-occurrences to analyze whether these are indeed re-victimizations or other dynamics of the ecosystem that even the ecosystem itself is not aware of. We notice, for example, that some victims are listed months or years apart, whereas others are reposted within days or weeks. We do not download the stolen data and examine the content of the listings as this is an ethical concern of ours where we do not want to download and store stolen victim data. Hence, we base our observations on matching the victim names.

One of our most urgent questions when looking at possible re-victimization is why we see some victims re-appearing.

We have some simplified hypotheses about it:

- Another cyber-attack: An actual re-victimization and thus a second round of Cyber Extortion / cyber-attack against the same victim has occurred. Either through potentially using the same point of entry or backdoor; or completely unrelated to the first occurrence.

- Re-use of access or data: The victim data has ‘travelled’ (leaked or sold to the underground) and is being used as leverage to try to extort the victim once more. Or the access has been sold to different buyers. Nevertheless, data or access is being re-used.

- Affiliate crossover: An affiliate has reused victim data between different Cy-X operations.

The last hypothesis might show how financially driven threat actors are and how desperate they might have become. We are sure that there might be other variations of our hypotheses, but we wanted to keep it as simple as possible for the following analysis. We wanted to explore whether we see patterns of re-victimizations between actors. We found over 100 occurrences where victims had been re-posted, either to the same or another group’s leak site.

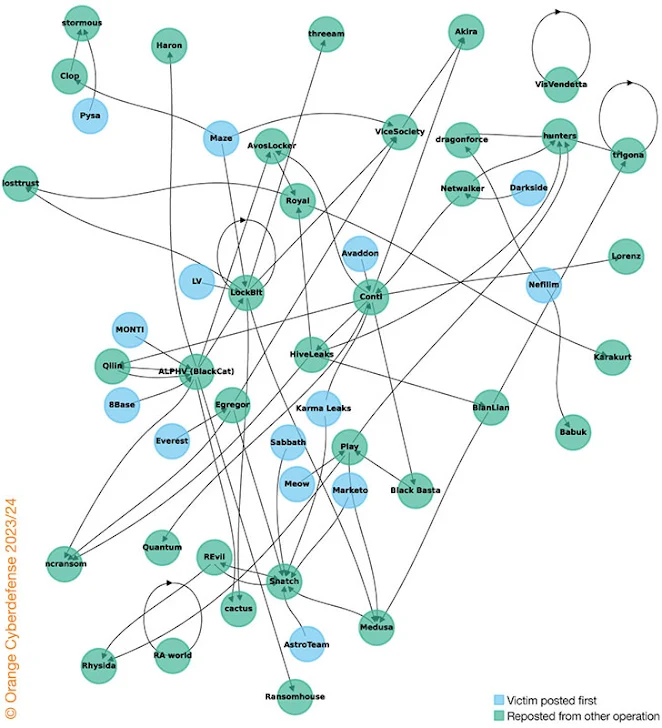

We created a network graph and added some colour coding to the nodes. The green nodes represent actors who were the second to post about a particular victim. They highlight the re-victimization. The blue nodes represent actors that act as the origin or first poster of a victim. When a Cy-X actor has been both, a first-time poster and second time poster, the node is by default green. The arrows are an additional indicator. Looking at a directed network graph of victim appearances we can see the direction of the re-victimization. Some Cy-X actors with circular references repost victims on their own data leak site. The analysis below is an abstract from our current research, we are planning to publish a more extensive analysis in our upcoming Cy-Xplorer, our annual Ransomware report.

As can be seen above in the network graph, several clusters catch one’s eye. The Snatch group for example demonstrates re-victimization activity by consistently re-posting victims from other Cy-X operations such as from AstroTeam, Meow, Sabbath, Karma Leaks, cactus, Quantum, Egregor and Marketo. Please remember, re-victimization refers to the phenomenon where a victim of a crime experiences additional harm or victimization in the future. In our consideration that means that victims experience the re-occurrence of for example unauthorized access and/or data exfiltration and/or data theft and/or extortion and/or encryption and/or damage to reputation, and/or financial loss and psychological harm etc.

In the three hypotheses, the victim will be victimized once more, experiencing one, several or all of the harms just listed. This is not about the technical sophistication of the attack itself but by purely being listed once again on a darkweb leak site, the victim organization is exposed again to several severe forms of harm.

If we continue studying the graph, we see another cluster, ALPHV’s, where we see that ALPHV re-posted victims from MONTI, 8Base and Qilin (in the latter the victim organization was posted in the same day at both leak sites, ALPHV and Qilin). And at the same time, victim organizations that appeared first on ALPHV’s leak site, were re-posted by various other operations such as AvosLocker, LockBit, Ransomhouse, incransom, Haron, cactus, etc. The arrows help to indicate directionality of the relationship, e.g. who acted first. Other clusters show very similar patterns that we will not dive into in this exploration. Nevertheless, the network graph and the above (partial) analysis show us the relationships and patterns of re-posting victim organizations. More specifically, this propagation of the same victim (not same incident) through the Cyber Extortion landscape reaffirms another theory that we have talked about in prior work, namely the “opportunistic nature” of Cyber Extortion. Cyber Extortion is a volume game and one way to ensure financial gain is to ‘play on different fronts’ in order to secure at least some form of payments. Additionally, on a high level, it shows how messy this ecosystem has become. All three of our hypotheses further shine light onto the unpredictability of the cybercrime ecosystem.

Consequently, re-victimization is not something that changes how Cyber Extortion works but it does show us the potential for different forms of re-victimizations, and thus unfortunately increases the suffering of victim organizations that have been experiencing a Cyber Extortion attack. And finally, these kinds of analyses help us to understand the dynamics of a cybercrime ecosystem, in this case the Cyber Extortion / Ransomware threat landscape and its threat actors.

As with a first-time cyber-attack, for victim organizations it is important to address your victim variables that determine the outcome of your victimhood. In short, your cyber practices, your digital footprint, the value your organization’s data has to you, the time a threat actor has access to your environment, the security controls you might have in place to increase the “noisiness” of data exfiltration; are all variables that impact the attractiveness of your organization to the opportunistic threat actors out there in cyber space.

This is a sample of our analysis. A more extensive review of the threat potential of Cyber Extortion, its main actors and the effect of law enforcement (as well as a ton of other interesting research topics like an analysis of the data obtained from our extensive vulnerability management operations and Hacktivism) can be found in the Security Navigator. Just fill in the form and get your download. It’s worth it!