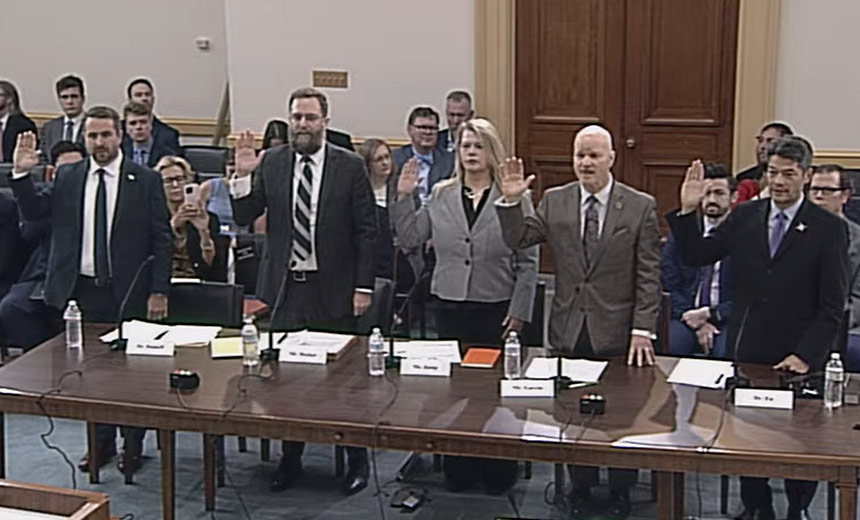

Industry Experts Testify Before Congressional Committee Examining Medical Devices

Massive workforce cuts at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and especially at the Food and Drug Administration, could hinder critical work involving medical device cybersecurity, potentially putting patient safety at risk and stiffing innovation, said some experts testifying during a Congressional hearing on Tuesday.

See Also: Frost Radar™ on Healthcare IoT Security in the United States

The hearing by the House Energy and Commerce Committee Subcommittee on Oversight examined cybersecurity challenges involving medical devices – especially older legacy products – but also to newer products entering the regulatory review pipeline.

Under legislation signed into law in December 2022, Congress expanded the FDA’s authority over medical device cybersecurity. Since then, the agency has implemented a review process evaluating the cybersecurity of new or modified medical devices as part of pre-market approval submissions (see: Raising the Regulatory Bar on Medical Device Cybersecurity).

“The FDA has been steadily raising the bar on cybersecurity expectations as part of its regulatory oversight,” testified Michelle Jump, CEO of MedSec, a security consulting and services firm.

But that progress is potentially at risk with uncertainty surrounding cuts being made at FDA, said some of the other witnesses.

HHS last week said the FDA will cut its workforce by about 3,500 full-time employees, as part of an overall reduction of 20,000 HHS employees (see: RKF Jr. Cuts at HHS Affect HIPAA, Cyber Response Units).

HHS last week said the reduction will not affect drug, medical device or food reviewers, nor impact inspectors, but Trump administration officials have not yet provided details of exactly which positions are on the chopping block.

Any reduction of the FDA’s review staff and other experts involved with the medical device work “would have a tremendous impact on cybersecurity … making pre-market and post-market management of cybersecurity more difficult,” testified Kevin Fu, professor at Northeastern University and director of its Archimedes Center for Healthcare and Medical Device Cybersecurity. Fu also served at the FDA during the COVID-19 pandemic as a special advisor.

“While I was acting director of medical device security at the FDA a few years ago, it was a skeleton crew of a small number of individuals,” Fu said. “Losing any of these subject matter experts would be difficult to address the next Contec kind of vulnerability or the next ransomware outage affecting hospitals across country,” he said.

A reduction of FDA’s staff could not only potentially hamper the agency’s device cybersecurity assessments, development of new cyber guidance and its response to newly discovered vulnerabilities – but also slow down the FDA’s overall review process for innovative medical technologies, witnesses said.

Additionally, the uncertainty of job security in the federal government could make the recruitment and retention of medical device cybersecurity experts more difficult in the future, Fu said.

Legacy Problems

Witnesses also pointed out that older or legacy medical devices, including those that are no longer supported by their vendors, often have potential security issues that put patient safety at risk – plus the security of the other IT systems and networks to which the devices are connected.

“Legacy devices are ubiquitous across our healthcare infrastructure but how many, which types, how secure – or not – these are all open questions existing in a vacuum of data,” testified Dr. Christian Dameff, a practicing physician and co-director of the UC San Diego Center for Healthcare Cybersecurity.

Dameff called for strengthening legal protections for ethical hackers researching medical device cybersecurity issues. Ethical hacking has led to the discovery of many critical vulnerabilities, including a hidden backdoor in a patient monitor – the CMS8000 – produced by Chinese manufacturer Contec (see: Alarming Backdoor Hiding in 2 Chinese Patient Monitors).

“No one knows how many CMS8000s there are in U.S. hospitals, or where they are,” Dameff said.

The uncertainty about how many millions of legacy devices overall are in use at U.S. hospitals and other medical facilities also underscores the need for the healthcare sector to map its inter-connections and co-dependencies, he said.

In fact, that national mapping project is underway by the cybersecurity working group of the Health Sector Coordinating Council, a private-public collaboration that serves as an advisory group to HHS, CISA and other federal agencies.

“Our expectation is to be done with this effort by this time next year. It needs to be done comprehensively, yet carefully, to ensure that we do not inadvertently reveal critical and potentially vulnerable elements of our critical infrastructure operations to our adversaries,” testified Greg Garcia, executive director of the HSCC’s cybersecurity working group (see: Mapping Health Sector Chokepoints Before the Next Big Attack).

But the cuts being made within HHS are not the only potential obstacles facing medical device cybersecurity issues – as well as larger healthcare sector cyber matters, another expert said.

Under a recent executive order, President Trump on March 7 disbanded 16 critical infrastructure policy advisory committees under which leaders from critical infrastructures and the federal government discussed and shared critical cybersecurity issues, testified Erik Decker, CIO of Intermountain Healthcare, and former co-chair of the HSCC CWG.

“We urgently need these reestablished, so we can get back to work securing our critical infrastructure without fear of our most sensitive vulnerabilities being public,” he said.